A Brief Guide to Laminitis

Causes, Management and Practical Tips for Prevention.

Please also see our information sheets on Equine Metabolic Syndrome and Cushings Disease (PPID)

What Happens in Laminitis

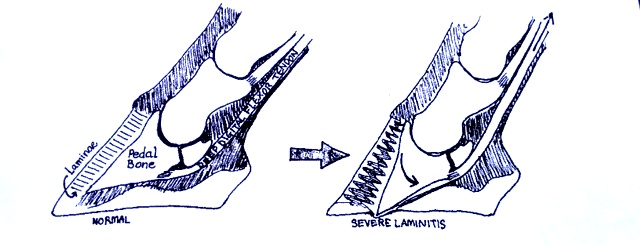

Inside a horses hoof lies the pedal bone (coffin bone), which is attached to the hoof capsule by millions of interlocking finger-like structures – the laminae. The processes involved in laminitis start to break down these vital attachments, and they begin to tear away from one another.

A horse exerts a vast amount of pressure on these structures – just standing, an average horse will be taking more than 150kg of its weight through each front foot – and that is before it takes a step. This force increases massively the faster the horse goes. Furthermore, the Deep Digital Flexor Tendon attaches to the back of the pedal bone, and exerts a huge rotating force. The only things resisting these massive forces are the laminae and the pressure from the ground.

In the worst cases of laminitis, the laminae are so weakened that the weight of the horse and the pull of its flexor tendons rips them apart and the pedal bone is forced through the sole. This is of course the extreme example, and relatively rare, but a whole spectrum exists from the mildest damage to the laminae to a fatal rotation.

There is a tendency for some people to dismiss the disease, simply because it is common – ‘he’s just got a touch of laminitis’ or ‘he always gets sore feet at this time of year’ and ‘I just keep him in for a day or two if he looks footy’ are comments we hear quite frequently. All laminitis is painful and I hope you agree that once you understand what is happening inside the foot of a horse or pony with laminitis, this seems somewhat flippant, and also rather unfair to the poor horse.

Rotation of the pedal bone

The way a horse has evolved, its foot is effectively the last joint of its middle finger, and it stands on the fingernail, which is the hoof capsule. If you imagine tearing away the fingernail from the finger, very slowly, this is the sort of pain experienced by a laminitic.

What might make me think my horse has laminitis?

Most people have an image of a horse leaning back on its heels, unable to move. This is a Very Bad Thing! There are earlier, much more subtle signs that are worth having at the back of your mind, as the earlier we can spot the disease the better:

- Shifting weight from foot to foot, often quite slowly and subtly.

- A short choppy (‘duck flappy’) stride on hard surfaces, especially when turning.

- Wanting to walk on the soft, avoiding gravel etc. May not want to walk or trot.

- Warm/hot feet.

- Reluctance to lift feet.

- Pronounced digital pulses – your vet can show you where to feel for these or go to the bottom of the page to watch Helen showing you how to find the digital pulse.

- Signs of distress such as fast breathing, sweating and laying down more than normal.

- And of course the leaning back ‘toe-relieving’ laminitic stance.

What Causes Laminitis?

Laminitis can develop for a number of reasons, and is currently a hot area of research. Often there is not a single cause, but many contributing factors:

Nutritional – Too many calories!

Other predisposing factors and triggers include:

- Insulin resistance / Equine Metabolic Syndrome ] 90% of laminitics have an

- Cushing’s Syndrome (PPID) ] underlying hormonal cause

- Poor shoeing, especially with…

- Too much fast work on hard ground / roads (also known as ‘road founder’).

- Carbohydrate overload/gorging grain

- Toxaemia or other disease (e.g. liver)

- Large doses of steroids, or stress.

- Reduction in workload, but not feed.

- Overload of the opposite leg as a consequence of another problem

Grass Laminitis – Latest Thoughts

If you eat a diet high in fat you don’t get diabetes tomorrow, but in 10 or more year’s time. This is the same in horses. A horse that has been over weight for a long time may suddenly get laminitis despite no sudden change in appearance. This is because insulin resistance has been developing with long term obesity and just reached the threshold level which, when combined with other factors like too much grass, causes laminitis.

We no longer think that it is the level of fructans in grass that is responsible for causing laminitis.

We now think of grass in terms of its calorific value instead and it is this calorie intake which needs limiting.

So pasture laminitis is now known to involve a degree of insulin resistance and shares the same final disease pathway as Cushing’s syndrome and Equine metabolic syndrome. The key factor in this pathway is insulin. High levels of insulin result in pro-inflammatory changes and vasoconstriction – reduced blood flow to the laminae and increases the risk of getting laminitis.

It is now strongly suspected that if a pregnant mare has poorly balanced nutrition – causing obesity – or a lack of vital vitamins and minerals her foal will be predisposed to insulin resistance and be at higher risk of developing laminitis for its whole life.

Management and Feeding

Severely restricting the volume of food a horse can eat is not ideal because horses are naturally trickle feeders. Long periods without food can result in boredom, stereotypy (wind sucking/weaving) and/or gastric ulcers.

Pasture management – revolves around trying to reduce the number of calories horses get from their grass. Peak seasonal growing times such as spring and autumn, when there is warm sunny weather accompanied by rainfall, result in carbohydrate rich grass with a high calorific value.

High Risk Grazing

- Lush grass

- Hay aftermath

- Long, dead-looking old grass.

- Frozen grass

Feeding Tips

- Limit the amount of grazing available by increasing the number of horses, reducing the size of the field or using a grazing muzzle

- Mow fields in the summer if they are not used for grazing or hay, to prevent them going to seed – don’t turn laminitics out onto this ‘winter-proud’. It looks dead but is still full of calories.

- Turn out onto an area which is small enough to be kept grazed short. Suitable grass looks ½ mud and ½ grass.

- Don’t be fooled into thinking there’s no grass – usually there’s only no grass because the horse is eating it as fast as it can grow!

- If you are having to mow your lawn then the grass is growing – if the field looks bare but you are mowing your lawn twice a week then the horses are eating a lot of grass!

- Use a weigh-tape every couple of weeks – they are useful to monitor if weight is going up or down.

- When stabled, feed hay which has been soaked for 12 hours to remove some of the soluble sugars, this means they can have more bulk for the same calories. Barley straw mixed with hay also helps give more bulk for fewer calories.

- Make sure the diet is balanced for vitamins and minerals, especially whilst feeding lots of low calorie fibre, e.g. Lo-Cal balancer daily.

Exercise helps reduce insulin resistance, try to ensure your horse gets a minimum of 30 minutes ACTIVE walking every day or gentle lunge.

Digital Pulse Video

Further queries please contact us.